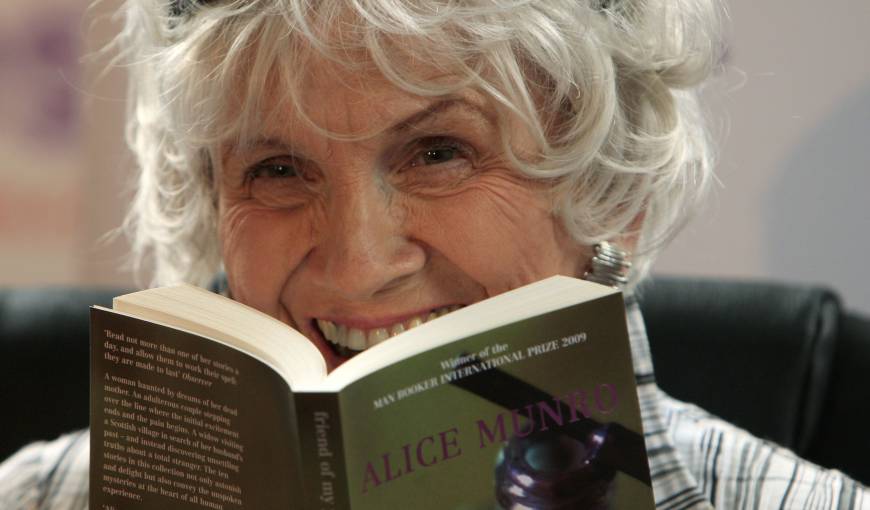

Canadian writer Alice Munro, a thorough but forgiving documenter of the human spirit, won the Nobel Prize in literature on Thursday for being a “master of the contemporary short story,” the Swedish Academy said. Munro is the first Canadian writer to receive the prestigious $1.2 million award since Saul Bellow, who won in 1976 and left for the U.S. as a boy.

Munro is the first Canadian writer to receive the prestigious $1.2 million award since Saul Bellow, who won in 1976 and left for the U.S. as a boy.

She is praised for her warmth, insight and compassion, and for capturing a wide range of lives and personalities without passing judgment on her characters.

Her writing has brought her numerous awards. She won a National Book Critics Circle prize for “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage,” and is a three-time winner of the Governor General’s prize, Canada’s highest literary honor.

“I knew I was in the running, yes, but I never thought I would win,” Munro said by telephone when contacted by The Canadian Press in Victoria, British Columbia.

The permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, Peter Englund, said, “She has taken an art form, the short story, which has tended to come a little bit in the shadow behind the novel, and she has cultivated it almost to perfection.”

Despite her vast success and an impressive list of literary prizes awarded over the past four decades, Munro, 82, remains as unassuming and modest as her characters. These are usually women who do not fit the normal stereotype of the beautiful, ravishing heroine, possibly reflecting the puritan values of her childhood.

“She is not a socialite. She is actually rarely seen in public, and does not go on book tours,” commented American literary critic David Homel.

As brilliant, dignified and elegant as Munro is, she is sometimes described as the complete opposite of another great dame of Canadian literature, Margaret Atwood.Her subjects and her writing style, such as a reliance on narration to describe the events in her books, have earned her the moniker “our Chekhov,” a term affectionately coined by Russian-American writer Cynthia Ozick.

Munro herself has said she writes about the “underbelly of relationships,” adding she sets her stories in Canada “because I live life here at a level of irritation which I would not achieve in a place that I knew less well.”

“There are no such things as big and little subjects,” she has said. “The major things, the evils, that exist in the world have a direct relationship to the evil that exists around a dining room table when people are doing things to each other.”

In a 2010 interview, she said she wanted readers “to feel something is astonishing — not the ‘what happens’ but the way everything happens,” she explained, adding that “long short story fictions do that best” for her as opposed to novels.

Munro is the 13th female literature laureate in the 112-year history of the Nobel Prizes.

Her published work often turns on the difference between Munro’s youth in Wingham, a conservative Canadian town west of Toronto, and her life after the social revolution of the 1960s.

In an interview in 2003, she described the ’60s as “wonderful.” It was “because, having been born in 1931, I was a little old, but not too old, and women like me after a couple of years were wearing miniskirts and prancing around,” she said.

Munro, the daughter of a fox farmer and a teacher, was born Alice Anne Laidlaw. She was a literary person in a nonliterary town, concealing her ambition like a forbidden passion.

She received a scholarship to study at the University of Western Ontario, majoring in journalism, and was still an undergraduate when she sold a story to CBC radio in Canada.

She dropped out of college to marry a fellow student, James Munro, had three children and became a full-time housewife. By her early 30s, she was so frightened and depressed she could barely write a full sentence.

Her good fortune was to open a bookstore with her husband in 1963. Stimulated by everything from the conversation of adults to simply filling out invoices, her narrative talents resurfaced, but her marriage collapsed.

Her first collection, “Dance of the Happy Shades,” came out in 1968 and won the Governor’s prize.

She later married Gerald Fremlin, a geographer.

Thfire.com Everyday news that matters

Thfire.com Everyday news that matters